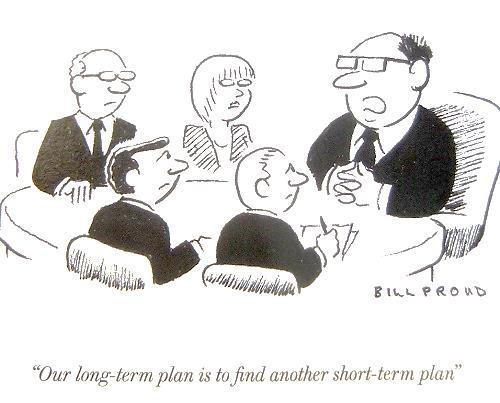

Despite the recent infusions of large amounts of public money into large financial institutions and the ongoing implicit state guarantees provided to the global financial system, the public interest continues to lack formal representation in banking. Moreover, the debate on corporate social responsibility remains dominated by the shareholder value paradigm. The following post discusses the origin of this paradigm and the legal position in most jurisdictions in relation to the pursuit of shareholder value. It also analyses the specific dangers adherence to shareholder value poses in the case of banks, before canvassing possible remedies.

The idea that the corporation exists to serve the exclusive interest of its shareholders remains the dominant framework in economics and finance (Shleifer and Vishny 1997). This view may be traced to Milton Friedman’s seminal article, in which he argued that the “there is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits” (Friedman 1970). Many studies into corporate governance theory and practice were conducted in the wake of this statement. The most famous of these, by Jensen and Meckling (1976), purports to provide empirical support for the benefits of limiting agency costs – that is, the costs imposed by managers on the ‘owners’ of firms they are entrusted to serve. This argument provided sustenance to another of Friedman’s conclusions; namely, that the “whole justification for permitting the corporate executive to be selected by the stockholders is that the executive is an agent serving the interests of his principal.”

Yet, these ideas – at least from a corporate law perspective – are deeply flawed, and the notion that shareholder wealth maximisation should be pursued to the exclusion of other interests remains arguably the most misleading mantra in corporate governance and finance. Generally, at law in most jurisdictions a corporate executive is not appointed, as Friedman claims, to “serve the interests of his principal” – she is appointed to serve the interests of the corporation, which constitutes a distinct entity with separate legal personality and its own interests (Johnston 2011). Accordingly, except in exceptional circumstances, boards of directors must discharge their duties to the corporation, not to shareholders (Stout 2012). Moreover, shareholders do not legally “own” corporations; they own property rights in the form of shares, which are intangible, tradable contractual rights granting certain limited benefits to their holders (Kay and Silbertson 1995). From the point of the law, therefore, shareholder value is not necessarily the appropriate paradigm through which to approach issues of corporate governance and strategy.

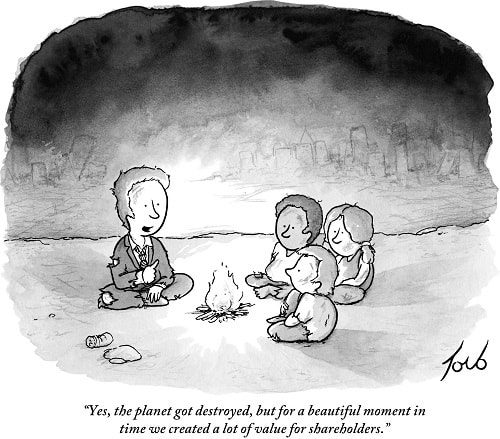

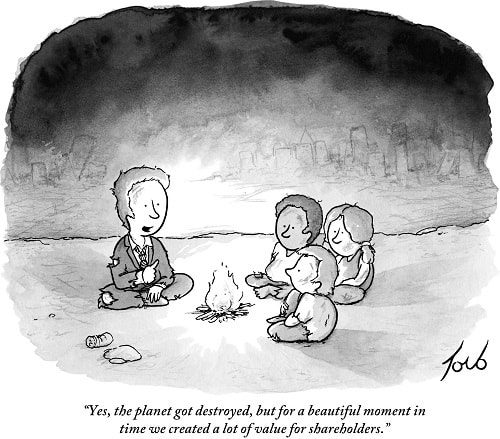

In the case of banks, maximising shareholder value may be even more misguided. First, unlike in the case of most other forms of corporation, there are explicit outside financial interests at stake in relation to the management and conduct of large banks. Banks perform critical utility functions in modern economies: they provide clearing and payment systems; act as stores of value; provide market liquidity; and are conduits for monetary policy transmission. Any disruption to their operations may therefore have far-reaching effects. Yet, their actions may impose costs on third parties which they cannot internalise and losses may quickly spillover into other areas of the economy. Because of this, banks are afforded very generous state-backed deposit-insurance schemes and lender of last resort facilities. They are also granted unique legal licenses to create liabilities (bank deposits) at will, which are exchangeable at par for state money. These advantages are reflected in the lower relative borrowing costs and higher credit ratings enjoyed by large financial institutions, which help shield them from competition and confer direct financial benefits on bank shareholders (Avgouleas and Cullen 2014). Whilst additional standards of regulation and conduct are imposed upon banks and their directors, these obligations are often limited and difficult to enforce.