How to strengthen the sustainability transparency framework for financial products

Introduction

Over the past years, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) raised major concerns:

- The flexibility left for defining key concepts (e.g. sustainable investment and the consideration of principal adverse impacts) leads asset managers to publish non comparable product reporting, opening the door to misleading statements.

- The classification introduced to determine the reporting requirements has been misused and Article 8 and 9 classifications have been presented as product labels.

- The absence of a concept of transition in SFDR led to a misleading definition of which investment should be considered as sustainable, as certain asset managers consider transitioning companies as sustainable investments.

- The current product disclosures focus on reporting sustainability characteristics, but do not require reporting the actual adverse impacts of each financial product.

As detailed in Finance Watch’s report “A guide to the next sustainable finance agenda”[1], these weaknesses are particularly problematic as they open the door to greenwashing practices and undermine the credibility of the sustainable finance framework as a whole.

On 4 December 2023, ESMA issued new RTS to improve disclosure requirements detailed in the delegated act and introduced the concept of transition finance through the disclosure of GHG emissions reduction targets. However, these adaptations shall not solve more fundamental concerns over the SFDR. On 15 September 2023, the Commission launched a consultation for the revision of SFDR L1, which includes a proposal for adapting key concepts and introducing new product categories. This is the opportunity to solve the inconsistencies and limitations of the regulation.

This position paper provides a comprehensive overview of Finance Watch’s proposed adaptations to SFDR and completes its response to the European Commission’s consultation. In a second position paper[2], Finance Watch explains how the revised transparency framework for financial products should align with MiFID, IDD and PRIIPS and their corresponding review.

Key Takeaways

- Transform SFDR into a disclosure and labeling regime

SFDR product disclosures should be preserved but the quality and relevance of data points should be reinforced. Policymakers should also extend it to a labeling regime based on four new categories.

- Align the fund naming rules with the SFDR product categories

The fund naming guidelines should leverage the criteria defined for each product category to prevent inconsistencies and simplify fund management rules.

I. Overview of proposed SFDR improvements in a broader context

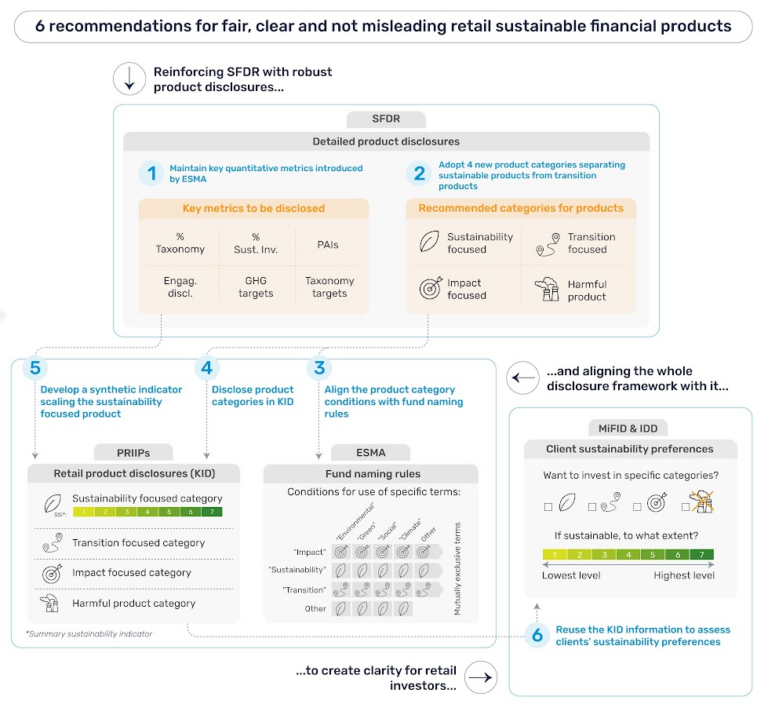

The diagram below highlights the key recommendations for resolving the weaknesses of SFDR and the retail investment transparency framework. Although the transparency framework is interconnected and must remain consistent overall, this position paper covers the product disclosure framework and focuses on the first three recommendations presented in the overview below. The other three recommendations to align the retail transparency framework with the proposed revision of SFDR are elaborated in a separate position paper[3].

II. Focus on the SFDR adaptations

Finance Watch recommends (1) preserving product disclosure requirements but reinforcing their quality and their relevance, as well as (2) extending the scope of SFDR to a labeling framework as per the four above categories.

SFDR already introduces a product disclosures template. However, the current product disclosures are lengthy and not designed in a way that can be easily understood by retail investors. Moreover, the disclosures include qualitative information difficult to use for comparing financial products which leads to different interpretations.

Yet, product disclosures remain important both for retail and corporate investors, although disclosures for retail investors should be tailored to target the most relevant data and facilitate interpretation of key ESG features. They can provide necessary tools for investors to adopt a sustainable/responsible investment strategy and understand how ESG characteristics are integrated. A large part of the disclosure adaptations should be made in the level 2 of SFDR and complement the first improvements already proposed by ESAs[4]. However, an adequate disclosure regime would still require certain adaptations to SFDR L1.

In parallel, the misuse of Article 8/9 classification highlights the need for clear labels that would be subject to minimum requirements and would emphasize the difference between sustainable investing and transition finance. This distinction may also pave the way for the development of requirements on how undertakings’ transition plans should be designed.

A. Adaptations to the disclosure regime (Recommendation 1)[5]

Yes, SFDR should not switch to a mere labeling framework given that sustainable investors will still need to be able to assess the different shades of sustainability. It cannot be assumed that a few labels will be sufficient to consider the level of sustainability of financial products as it would likely only refer to a limited set of minimum criteria.

A principal adverse impact (PAI) statement should be provided for each financial product in the periodic statement, which requires adapting provisions in SFDR L1. The current template only instructs including unstructured information on how PAIs are being considered, which does not provide sufficiently comparable information. Financial market participants (FMPs) are indeed required to describe their policies to identify and prioritize PAIs on sustainability factors, but there are no minimum requirements defining when it can be stated that adverse impacts are considered.

Moreover, SFDR product disclosures positively reflect where adverse impacts are considered, but do not reflect other impacts that may not be considered. Understanding the sustainability level of a product can only be done through a combined understanding of investments that are made in sustainable activities (e.g. through the Taxonomy and sustainable investment metrics) as well as investments that are made in harmful activities.

Finally, costs associated with reporting adverse impacts at product level would be limited as FMPs are already storing the information for their existing PAI statement at entity level.

Yes, all the financial products should at least report on their adverse impacts. It is particularly important as the non-sustainable products will be expected to have higher negative impacts and investors should be able to identify them. The disclosure of PAIs should therefore be made mandatory, while the disclosure of metrics reflecting positive impacts should be optional (but mandatory for specific categories of products). Today, it seems paradoxical that only sustainable financial products – promoting their ESG characteristics – are subject to additional reporting costs.

No, the introduction of a materiality assessment on PAIs would leave an important reliance on the quality of such exercise. The current mandatory PAIs – for entity PAI statements – should not be switched to “voluntary/subject to materiality assessment”.

Yes, product categories have the potential of differentiating between purposes of sustainable investing, providing a simplified overview on the integration of ESG characteristics for retail investors, and ending the confusion between (1) green products, (2) products considering ESG risks and (3) transition finance products. However, this would only happen if an adequate classification and minimum requirements are developed. The assimilation of the current SFDR categories to a form of sustainability label without specifying minimum criteria poses a real problem of transparency and greenwashing.

A transition focused category: In the current framework, the possible inclusion of companies in the fossil fuel sector in the definition of sustainable investment, under the rationale that they take transition actions, affects the credibility of sustainable finance. A distinctive category should be available and focus on obligations of means to support the transition. This should include, among others, minimum engagement on ESG concerns, such as the consideration of the achievement of transition plans when voting on directors’ variable remuneration, and divestment strategies for “off track” investee companies. Obligations of means should be favored over obligations of result, given the role and powers of investors to influence investees’ behaviours.

A sustainability focused category: While investing in the transition of existing activities is a necessary element to move to a sustainable economy, the development of activities or investments that are already sustainable and investments in specific sustainable projects/solutions are also necessary. A category of products focusing on investing in sustainable activities should be available and respect minimum requirements in terms of sustainable investment, taxonomy alignment and exclusion of harming activities.

An impact focused category: The integration of impact finance to the SFDR framework is the opportunity of tailoring SFDR for non-traditional financial institutions that base their investment decision-making process on qualitative and principle-based factors rather than traditional quantitative factors. Yet, impact finance requires a strong corporate behavior and business culture that may be difficult to translate into mandatory practices. The notion of impact should therefore be clearly defined to prevent assimilating it to traditional investments and actually cover the niche market of “impact finance” while respecting the three recognised principles: intentionality, measurability and additionality.

A harmful product category: Besides ‘positive’ categories, a classification for products socially/environmentally harmful would provide investors with the possibility to exclude harmful investments from their portfolio. At the same time, while positive categories would be voluntary, the negative category should be a mandatory classification when a product meets the criteria. This category would then push asset managers to take the necessary actions for their products to meet the transition focused category and not fall under the harmful category.

Yes, this will prevent situations where asset managers will mix sustainable investments and engagement on investments that are already sustainable in order to fall under both categories and more easily meet the sustainability preferences of their clients. Such practice could lead to unclear fund strategies, a limited use of available transition levers and concentration of engagement on companies that are already sustainable. A mutually exclusive classification would also support the definition of more ambitious minimum requirements for each of the categories.

A “theme investing” category should not be proposed at the same level as the previously mentioned categories as it rather consists in focusing on specific factors underlying the transition or sustainable solutions. Investing in a specific theme could be done under each “positive” category, which would limit the possibility to make them mutually exclusive. Yet, theme investing can provide investors with a better understanding of the features of an investment strategy. For example, certain FMPs have developed investment strategies focusing on specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They should therefore still have the flexibility to promote a focus on certain SDGs if they wish.

A category of product considering principal adverse impacts only could appear to respond to the investors’ interest not to harm. However, it could be interpreted or marketed as a ‘light green’ category although it does not provide a positive impact. The introduction of an intermediate category between neutral and sustainability focused products could lead to nudging and decrease clients’ declared sustainability preferences. Finally, the notion of “consideration of PAI” is currently not defined and its clarification would appear challenging given its interaction with the “do not significantly harm” criteria of the Taxonomy and SFDR. As an alternative, we therefore support the introduction of a harmful product category.

III. Focus on the fund naming rules

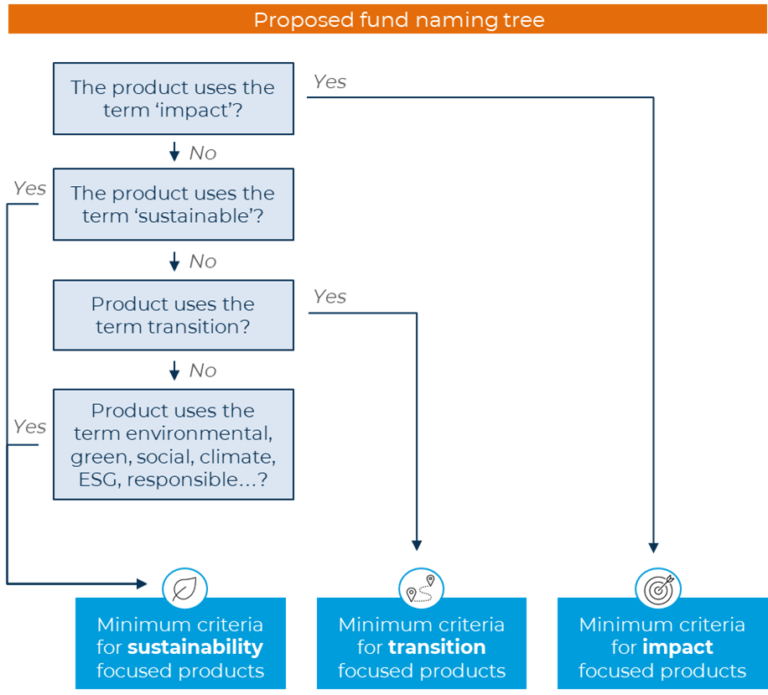

Finance Watch recommends adapting the fund naming guidelines to leverage from the requirements defined under each product category to ensure consistency between the category of a product and its naming.

ESMA published its final fund naming guidelines on 14 December 2023. In the updated document, ESMA proposed a minimum percentage of 80% of investments used to meet the sustainability characteristics or objectives for funds to be named “sustainable”. The funds are also required to meet the exclusion criteria of the Paris-aligned benchmarks (for products using the term “sustainable”, “environmental” or “social”) or the more flexible exclusion criteria of the transition-aligned benchmarks (for products using the term “transition”).

While fund naming should be monitored, the current rules lead to discrepancies between the naming rules and the current internal sustainable and responsible investment policies of the FMPs. The implementation of minimum criteria for the new product categories is therefore the opportunity to solve this complex situation.

A. Simplification of rules (Recommendation 3)

Yes, the use of specific terms in the name of the financial products should be regulated to prevent situations where FMPs would market sustainable characteristics for their products without respecting minimum criteria and possibly mislead investors.

Yes, as soon as minimum requirements are defined for each product category, a strict correspondence between the fund naming rules and the category should apply. A simplified overview of how fund naming rules should leverage from the categories criteria is included in the annex. This would simplify the monitoring of mandatory thresholds both by FMPs and the supervisory authorities. To ensure an adequate enforcement of the rules, funds using ESG-related terms in their names should therefore not only respect the minimum criteria but also be categorized under the relevant product category. This implies that the terms “sustainable”, “transition” and “impact” should not be used together for the name of a fund, given that the product categories should be mutually exclusive.

Conclusion

The proposed framework is a first step to ensure that SFDR is better integrated into the sustainable finance legislative framework. It consistently links transparency, product labeling and fund naming rules in a way that prevents misleading behaviors and facilitates the application of the rules by FMPs. Yet, the product transparency framework still needs to connect with retail investors’ needs, as detailed in our separate position paper.

Vincent Vandeloise, Senior Research & Advocacy Officer at Finance Watch

+32 2 880 04 37

Download the PDF version

Footnotes

[1] Finance Watch, A guide to the next sustainable finance agenda, January 2024.

[2] Finance Watch, Sustainable investing: Tailoring the transparency framework for retail investors, May 2024.

[3] Finance Watch, Sustainable investing: Tailoring the transparency framework for retail investors, May 2024.

[4] European Supervisory Authorities, Final report on draft Regulatory Technical Standards, December 2023.

[5] As per the figure presented on page 3.